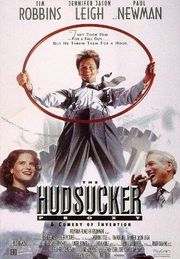

The Hudsucker Proxy

| The Hudsucker Proxy | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Joel Coen Ethan Coen (uncredited) |

| Produced by | Joel Coen Ethan Coen |

| Written by | Joel Coen Ethan Coen Sam Raimi |

| Starring | Tim Robbins Jennifer Jason Leigh Paul Newman Jim True-Frost |

| Music by | Carter Burwell |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Editing by | Thom Noble |

| Studio | Silver Pictures Working Title Films |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. (USA) PolyGram Filmed Entertainment (non-USA) |

| Release date(s) | United States: March 11, 1994 United Kingdom: September 2, 1994 |

| Running time | 111 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom Germany United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25-40 million[1] |

| Gross revenue | $2.81 million |

The Hudsucker Proxy is a 1994 screwball comedy/fantasy film written, produced and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen. The script was co-written by Sam Raimi, who also served as the second unit director. The Hudsucker Proxy stars Tim Robbins, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Paul Newman and Jim True-Frost, and depicts the story of Norville Barnes, a naive business graduate who is installed as president of a manufacturing company as part of a stock scam.

The Coen brothers and Raimi had initially finished the script in 1985, but production did not start until 1991, when Joel Silver acquired the script for Silver Pictures. Warner Bros. subsequently agreed to cover distribution duties, with further financing coming from PolyGram Filmed Entertainment and Working Title Films. Filming at Carolco Studios in Wilmington, North Carolina lasted from November 1992 to March 1993. The New York City scale model set was designed by Micheal J. McAlister and Mark Stetson, with further effects provided by The Computer Film Company. The Hudsucker Proxy was released in March 1994 with a box office bomb performance and received mixed reviews from critics.

Contents |

Plot

In December 1958, Norville Barnes, a business college graduate from Muncie, Indiana, arrives in New York City looking for a job. He struggles, due to lack of experience, and becomes a mailroom clerk at Hudsucker Industries. After the company founder and president, Waring Hudsucker, unexpectedly commits suicide by jumping out of a top floor window, Sidney J. Mussburger, a ruthless member of the board of directors, mounts a scheme to buy up the controlling interest in the company's stock before Hudsucker's shares are made available to buy for the public. Hoping to temporarily depress the stock price, Mussburger installs Norville as a proxy for the deceased president.

Norville wishes to fast track an invention he has been working on which appears to be a simple circle. Mussburger takes Norville for an idiot and tries to ascertain his intelligence. Amy Archer, a reporter for the Manhattan Argus, is assigned to write a story about Norville. She gets a job at Hudsucker Industries as Norville's personal secretary, after disguising herself as another desperate graduate from Muncie. One night, Amy searches the building to find clues and meets Moses, a man who runs the building's giant clock and knows "just about anything if it concerns Hudsucker". He tells Amy the board's plot for Norville, who takes the story back to her Chief, but he does not believe it. At the Hudsucker ball, Norville accidentally insults some stockholders.

The other executives decide to accept Norville's invention for the hula hoop, in the hope that it will depress the company's stock. However, the hula hoop brings the company greater success than before. Amy is infuriated over Norville's new attitude and leaves him. Buzz, the eager elevator operator, pitches a new invention: the flexi-straw. Norville does not like it and fires Buzz. Meanwhile, the Hudsucker janitor, Aloysius, discovers Amy's true identity and informs Mussburger. Mussburger reveals her secret to Norville and tells him that he will be dismissed as president after the new year. Mussburger also convinces the board that Norville is insane and must be sent to the local psychiatric hospital.

On New Year's Eve, Amy finds a drunk Norville at a beatnik bar. She apologizes, but he storms out of the place and is chased by an angry mob led by Buzz, who was led by Mussburger to believe that Norville stole the hula hoop idea from him. Norville escapes to the top floor of the Hudsucker skyscraper and changes back into his mailroom uniform. He climbs out on the ledge, where Aloysius locks Norville out and watches as he slips and falls off the building at the strike of midnight. Suddenly, Moses stops the clock and time freezes. Waring Hudsucker appears to Norville as an angel and tells him that due to a legal document, Hudsucker's shares would go to his immediate successor: Norville. Meanwhile, Moses fights and defeats Aloysius inside, allowing Norville to fall safely to the ground. He then reconciles his love with Amy. As 1959 progresses, Mussburger is sent to the asylum. Norville goes on with a new invention: the frisbee.

Development

Writing

The Coen brothers first met Sam Raimi when Joel Coen worked as an assistant editor on Raimi's The Evil Dead (1981). Together, they began writing the script for The Hudsucker Proxy in 1981,[2] and continued during the filming of Crimewave (1985),[3] and post-production on Blood Simple (1985), in which Joel and Ethan Coen shared a house with Raimi. The Coens and Raimi were inspired by the films of Preston Sturges, such as Christmas in July (1940) and the Hollywood satire, Sullivan's Travels.[4] The sentimental tone and decency of ordinary men as heroes was influenced by films of Frank Capra, like Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Meet John Doe (1941) and It's a Wonderful Life (1946). The dialogue is a homage to Howard Hawks' His Girl Friday (1940), while Jennifer Jason Leigh's performance as fast-talking reporter Amy Archer is reminiscent of Rosalind Russell and Katharine Hepburn, in both the physical and vocal mannerisms.[4] Other movies that observers found references to include Executive Suite (1954) and Sweet Smell of Success (1957).[5] as well as the Broadway play How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.

One film critic described the numerous influences: "From his infelicitous name to his physical clumsiness, Norville Barnes is a Preston Sturges hero trapped in a Frank Capra story, and never should that twain meet, especially not in a world that seems to have been created by Fritz Lang — the mechanistic monstrousness of the mailroom contrasted with the Bauhaus gigantism of the corporate offices perfectly matches the boss-labour split in Metropolis (1927)."[6] An interviewer proposed that the characters represent Capitalism versus Labour economics. Joel Coen replied: "Maybe the characters do embody those grand themes you mentioned, but that question is independent of whether or not we're interested in them - and we're not."[1] The Hudsucker Proxy presents various narrative motifs pertaining to the Rota Fortunae and visual motifs concerning the shape of circles. This includes Moses' monologue at the beginning, the Hudsucker Clock, Mussburger's wristwatch, the inventions of both the hoola hoop and frisbee, as well as Norville and Amy's conversation about Karma.[5]

The first image the Coens and Raimi conceived was of Norville Barnes about to jump from the window of a skyscraper and then they had to figure out how he got there and how to save him.[7] The inclusion of the hula hoop came as a result of a plot device. Joel remembers, "We had to come up with something that Norville was going to invent that on the face of it was ridiculous. Something that would seem, by any sort of rational measure, to be doomed to failure, but something that on the other hand the audience already knew was going to be a phenomenal success."[6] Ethan said, "The whole circle motif was built into the design of the movie, and that just made it seem more appropriate."[6] Joel: "What grew out of that was the design element which drives the movie. The tension between vertical lines and circles; you have these tall buildings, then these circles everywhere which are echoed in the plot...in the structure of the movie itself. It starts with the end and circles back to the beginning, with a big flashback."[6] It took the Coens and Raimi three months to write the screenplay. As early as 1985, the Coens were quoted as saying that an upcoming project "takes place in the late Fifties in a skyscraper and is about Big Business. The characters talk fast and wear sharp clothes."[6]

Despite having finished the script in 1985, Joel explained, "We couldn't make Hudsucker back then because we weren't that popular yet. Plus, the script was too expensive and we had just completed Blood Simple, which was an independent film."[8] After completing Barton Fink (1991), the Coens were looking forward to doing a more mainstream film.[9] The Hudsucker Proxy was revived and the Coens and Raimi performed a brief rewrite. Producer Joel Silver, a fan of the Coens' previous films, acquired the script for his production company, Silver Pictures, and pitched the project at Warner Bros. Pictures. Silver also allowed the Coens complete artistic control.[7]

Production

Joel Silver's first choice for Norville Barnes was Tom Cruise, but the Coens persisted in a desire to cast Tim Robbins.[10] Winona Ryder and Bridget Fonda were in competition for the role of Amy Archer before Jennifer Jason Leigh was cast.[5] Leigh had previously auditioned for a role in the Coens's Miller's Crossing and Barton Fink. Her failed auditions prompted the Coens to cast her in The Hudsucker Proxy.[8] When casting the role of Sidney Mussburger, "Warner Bros. suggested all sorts of names," remembered Joel. "A lot of them were comedians who were clearly wrong. Mussburger is the bad guy and Paul Newman brought that character to life."[8] However, the Coens first offered the role to Clint Eastwood, but he was forced to turn it down due to scheduling conflicts.[11]

Once Newman and Robbins signed on, PolyGram Filmed Entertainment and Working Title Films agreed to co-finance the film with Warner Bros. and Silver Pictures.[12] The film was shot on sound stages at Carolco Studios in Wilmington, North Carolina beginning on November 31, 1992. With Raimi as second unit director, he shot the hula hoop sequence and Waring Hudsucker's suicide.[8] Production designer Dennis Gassner was influenced by fascist architecture, particularly the work of Albert Speer, as well as Terry Gilliam's Brazil (1985),[7] Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art Deco movement.[13] Principal photography ended on March 18, 1993.[8]

In addition, numerous sequences were filmed in downtown Chicago, particularly in the Merchandise Mart lobby and the Hilton Chicago grand ballroom.

Visual effects

The visual effects supervisor was Micheal J. McAlister (Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Willow) with Mark Stetson (Superman Returns, Peter Pan) as miniatures supervisor. Peter Chesney, mechanical effects designer on many Coen brothers films, created a pair of 16-foot angel wings for actor Charles Durning, who portrayed Waring Hudsucker. "I made a complicated steel armature with a lot of electric motors to time everything so he can fold up his wings, unfold them and flap them about. Then we covered them with real duck and turkey feathers," says Chesney. "We modeled them after photographs of a hovering dove landing in slow motion."[14] The buildings in the background (designed by McAlister and Stetson) were 1:24 scale models, shot separately and merged in post-production. To lengthen the sequence, the model of the Hudsucker building was the equivalent of 90 stories, not 45.[15]

Despite the New York City setting, additional skyscrapers in Chicago, Illinois provided inspiration for the opening sequence of the skyline, such as the Merchandise Mart, Aon Center. Skyscrapers from New York City included the Chanin Building, the Fred F. French Building and One Wall Street, Manhattan. "We took all our favorite buildings in New York from where they actually stood and sort of put them into one neighborhood," Gassner continued, "a fantasy vision which adds to the atmosphere and flavor."[13] The work of The Computer Film Company (supervised by Janek Sirrs) included manipulations of the zoom-in shot of Norville at the beginning, as well as CGI snow and composites of the falling sequences.[13]

To create the two suicide falls, the miniature New York set was hung sideways to allow full movement along the heights of the buildings. McAlister calculated that such a drop would take seven seconds, but for dramatic purposes it was extended to around thirty. Problems occurred when the Coens and cinematographer Roger Deakins decided that these shots would be more effective with a wide-angle lens. "The buildings had been designed for an 18 mm lens, but as we tried a 14 mm lens, and then a 10 mm, we liked the shots more and more."[13] However, the wider amount of vision meant that the edges of the frame went beyond the fringes of the model city, leaving empty spaces with no buildings. In the end, extra buildings were created from putting the one-sided buildings together and placing them at the edges. Charles Durning's fall was shot conventionally, but because Tim Robbins had to stop abruptly at the camera, his was shot in reverse as he was pulled away from the camera.[13]

Soundtrack

| Original Motion Picture Soundtrack: The Hudsucker Proxy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack by Carter Burwell | ||||

| Released | March 15, 1994 | |||

| Genre | Film score | |||

| Length | 29:28 | |||

| Label | Varèse Sarabande | |||

| Professional reviews | ||||

|

||||

| Coen Brothers film soundtracks chronology | ||||

|

||||

Some of the score to The Hudsucker Proxy was written by Carter Burwell, the fifth of his collaborations with the Coen Brothers. Much of the source material for the score comes from the "Adagio" and "Phrygia" movements of the ballet Spartacus by Aram Khachaturian. Khachaturian's "Sabre Dance" is also used, when the boy is the first to try the hula hoop.

- Track listing

- "Prologue" (Khachaturian) – 3:20

- "Norville Suite" – 3:53

- "Waring's Descent" – 0:27

- "The Hud Sleeps" – 2:13

- "Light Lunch" (Khachaturian) – 1:38

- "The Wheel Turns" – 0:52

- "The Hula Hoop" (Khachaturian) – 4:10

- "Useful" – 0:40

- "Walk Of Shame" – 1:22

- "Blue Letter" – 0:43

- "A Long Way Down" – 1:46

- "The Chase" – 1:02

- "Norville's End" – 3:52

- "Epilogue" (Khachaturian) – 2:08

- "Norville's Reprise" – 1:22

Other songs used in the film but not on the soundtrack album include:

- "Memories Are Made of This", performed by Peter Gallagher as Vic Tenetta, the party singer

- "In a Sentimental Mood", performed by Duke Ellington

- "Flying Home", performed by Duke Ellington

- "Carmen", performed by Grace Bumbry; used in dream dance sequence.

The classical music used was:

- Georges Bizet, Habañera from Carmen

- Luigi Boccherini, Minuet (3rd movt) from String Quintet in E, Op.11 No.5

- Frédéric Chopin Chopin Waltz (Waltz No.1 in E-flat "Grande valse brillante", Op.18 B62) from Les Sylphides

- Aram Khachaturian, Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia from Spartacus Suite No.2

- Aram Khachaturian, Sabre Dance from Gayane Suite No.3

- Peter Tchaikovsky, Waltz from Swan Lake

Release

Warner Bros. held test screenings for The Hudsucker Proxy and audience comments were largely mixed. The studio suggested re-shoots, but the Coens, who held final cut privilege, refused because they were very nervous working with their biggest budget to date and were eager for mainstream success. The producers eventually added footage that had been cut and also shot minor pick-ups for the ending.[8] Variety magazine claimed that the pick-ups were done to try to save the film because Warner Bros. feared it was going to be a box office bomb. Joel Coen addressed the issue in an interview: "First of all, they weren't reshoots. They were a little bit of additional footage. We wanted to shoot a fight scene at the end of the movie. It was the product of something we discovered editing the movie, not previewing it. We've done additional shooting on every movie, so it's normal."[8]

The film premiered in January 1994 at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.[16] In addition, The Hudsucker Proxy was screened at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival[17] on May 12, 1994. The film was in competition for the Palme d'Or, but lost to Pulp Fiction.[18] The Hudsucker Proxy was released on March 11, 1994, and only grossed $2,816,518 the United States.[19] The production budget was officially set at $25 million,[8] although, it was reported to have increased to $40 million for marketing and promotion purposes. Nonetheless, the film was a box office bomb.[4] Response from critics were also mixed. Based on 37 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, 59% of the reviewers enjoyed the film.[20]

Roger Ebert praised the production design, scale model work, matte paintings, cinematography and characters. "But the problem with the movie is that it's all surface and no substance," Ebert wrote. "Not even the slightest attempt is made to suggest that the film takes its own story seriously. Everything is style. The performances seem deliberately angled as satire."[21] Desson Thomson of The Washington Post described The Hudsucker Proxy as being "pointlessly flashy and compulsively overloaded with references to films of the 1930s. Missing in this film's performances is a sense of humanity, the crucial ingredient in the movies Hudsucker is clearly trying to evoke. Hudsucker isn't the real thing at all. It's just a proxy."[22]

Todd McCarthy, writing in Variety, called the film "one of the most inspired and technically stunning pastiches of old Hollywood pictures ever to come out of the New Hollywood. But a pastiche it remains, as nearly everything in the Coen brothers' latest and biggest film seems like a wizardly but artificial synthesis, leaving a hole in the middle where some emotion and humanity should be."[23] James Berardinelli gave a largely positive review. "The Hudsucker Proxy skewers Big Business on the same shaft that Robert Altman ran Hollywood through with The Player. From the Brazil-like scenes in the cavernous mail room to the convoluted machinations in the board room, this film is pure satire of the nastiest and most enjoyable sort. In this surreal world of 1958 can be found many of the issues confronting large corporations in the 1990s, all twisted to match the filmmakers' vision."[24]

Warner Home Video released The Hudsucker Proxy on DVD in May 1999. No featurettes were included.[25]

A musical with book and lyrics by Glenn Slater and music by Stephen A. Weiner has been a work-in-progress since 2001. Stephenaweiner.com

References

- Ronald Bergan (2000). The Coen Brothers. New York City: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-254-5.

- Josh Levin (2000). The Coen Brothers: The Story of Two American Filmmakers. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-424-7.

- James Mottram (2000). The Coen Brothers: The Life of the Mind. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's, Inc. ISBN 1-57488-273-2.

- John Kenneth Muir (2004). The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi. New York City: Applause: Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 1-55783-607-8.

- Eddie Robson (2003). Coen Brothers. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 1-57488-273-2.

- Bill Warren (2000). The Evil Dead Companion. London: Titan Books. ISBN 0-312-27501-3.

- Paul A. Woods (2003). Joel & Ethan Coen: Blood Siblings. London: Plexus. ISBN 0-85965-339-0.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bergan, pp. 24, 36

- ↑ Muir, pp. 77

- ↑ Warren, pp. 101-102

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Levin, pp. 103-118

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Mottram, pp. 93-113

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Woods, pp. 125-135

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Bergan, pp. 148-162

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Woods, pp. 9-10, 122-124

- ↑ Juliann Garey (1993-02-05). "Coen to Extremes". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,305444,00.html. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ Anne Thompson (2007-11-15). "Coen brothers keep it real". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117976123. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Leonard Klady (1993-07-13). "DeVito looking to get 'Shorty' into production". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR108653.html?categoryid=13&cs=1&query=devito+looking+to+get+shorty. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Nisid Hajari (1994-04-01). "Beavis and Egghead". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,301615,00.html. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Robson, pp. 139-142

- ↑ Staff (1993-01-18). "Hollywood's still playing for effect". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR103029. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ George Mannes (1994-04-15). "The 'Hud' Thud". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,301802,00.html. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ Caryn James (1994-01-25). "Critic's Notebook; For Sundance, Struggle to Survive Success". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: The Hudsucker Proxy". festival-cannes.com. http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/3007961/year/1994.html. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ↑ Staff (1994-04-21). "Euro pix man Cannes". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR120356. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ "The Hudsucker Proxy". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=hudsuckerproxy.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ↑ "The Hudsucker Proxy". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/hudsucker_proxy/. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (1994-05-25). "The Hudsucker Proxy". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19940325/REVIEWS/403250301/1023. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ Desson Thomson (1994-03-25). "The Hudsucker Proxy". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Todd McCarthy (1994-01-31). "The Hudsucker Proxy". Variety. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117902311.html?categoryid=31&cs=1. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ James Berardinelli. "The Hudsucker Proxy". ReelViews.net. http://www.reelviews.net/movies/h/hudsucker.html. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ "The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)". Amazon.com. http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B00000ING2/. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

Further reading

- Mark Cotta Vaz; Patricia Rose Duignan (November 1996). Industrial Light & Magic: Into the Digital Realm. Hong Kong: Del Ray Books. ISBN 0-345-38152-1.

External links

- The Hudsucker Proxy at the Internet Movie Database

- The Hudsucker Proxy at Allmovie

- The Hudsucker Proxy at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Hudsucker Proxy at Box Office Mojo

- Richard Schickel (1994-03-14). "Half-Baked in Corporate Hell". Time. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,980305,00.html.

- Owen Gleiberman (1994-03-11). "Lord of the Ring". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,301350,00.html.

|

||||||||||||||